Welcome to the monetized playground.

For years, parents on YouTube have turned “just being a family” into a content strategy — and for a while, the internet has eaten it up. Daily vlogs. Gender reveals, and toddler tantrums with thumbnail-ready tears. Childhood was content. Privacy? Optional.

Now, the backlash is growing — not just from critics or lawmakers, but from the kids themselves. The stars of those cozy morning routines are older now, and they’re asking: Why didn’t I get a cut? Why was I filmed crying? Why did strangers know my bedtime routine?

California heard them. Tennessee…may have heard and fled.

A Short History of Family Vlogging: Cute Until it Wasn’t

In the golden age of YouTube, a camera and some kids were all you needed to make it big. Parents leaned into authenticity, filming diaper blowouts, lost teeth, and scraped knees like they were box office gold. And for a while, they were.

But as the genre matured, so did its critics. Vlogs blurred into reality TV. Emotional breakdowns got edited for comedic effect. Family milestones got packaged into profitable arcs, and behind the scenes, the ethics crumbled.

Piper Rockelle’s child influencer squad. Ruby Franke’s abusive “discipline” regime. DaddyOFive’s “prank” channel that landed the creators in a custody battle. At best, it was exploitative. At worst, it was criminal.

Meanwhile, audiences were growing uneasy, especially Gen Z, who saw less “relatable mom content” and more unpaid child labor, filmed and uploaded in high definition.

The Dangers Beyond the Screen

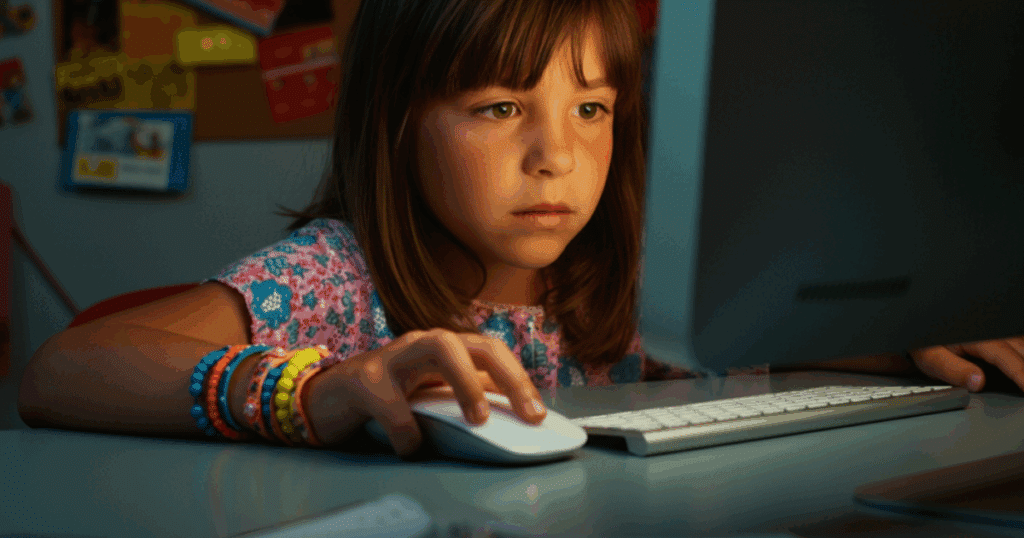

The harm of family vlogging doesn’t end when the camera stops recording. The most disturbing consequences happen after upload, when a child’s face — and entire personality — becomes public property.

Kids grow up in a surveillance state, and don’t know it. Being filmed isn’t inherently traumatic. But being filmed constantly, in every mood, every milestone, every vulnerable moment — without understanding the stakes — turns a home into a film set and a childhood into a product.

Most “content kids” don’t get to choose what’s shared. Their first words, their potty-training setbacks, their tears after a bad day — all uploaded, indexed, and immortalized for millions to see. Not just now. Forever.

By the time they’re old enough to understand what “privacy” even means, their digital footprint is already a mile long.

In a Cosmopolitan Australia article, Vanessa, a former child influencer, recounted her experience of being featured in her mother’s blog and social media content throughout her childhood. She described the pressure to maintain a perfect image and the lack of autonomy over her own life.

Vanessa said, “Sometimes I didn’t know where the separation was between what was real and what was curated for social media.”

Privacy? Optional. Oversharing? Expected.

Many family vloggers film inside their homes, showcasing bedrooms, bathrooms, meal times, and daily routines. Some go further, sharing medical updates, emotional breakdowns, and deeply personal information: allergies, school schedules, developmental diagnoses.

This level of exposure gives strangers more information than most parents would even share with a school nurse. And it’s often done for engagement, not necessity.

- Street names and schools get shown in back-to-school videos.

- Favorite parks and gyms show up in “day in the life” posts.

- Real names, birthdays, and faces of other family and friends get casually doxxed in the captions.

No minor should be this easy to track. But on family channels, the breadcrumbs are everywhere.

And People are Watching — Not All of Them Innocently

When you publish a video of a six-year-old changing into a swimsuit or a toddler sobbing mid-meltdown, you may think you’re documenting real life. But predators see something else: access.

The comment sections of these videos often fill with chilling engagement:

- “She’s so mature for her age.”

- “What’s her name again?”

- “Time stamp 4:32 🥵”

Despite growing awareness around online child exploitation, many experts argue that systemic protections remain dangerously insufficient. While public debates rage over content ethics and parental responsibility, predators continue to exploit the loopholes, often undetected and largely unchallenged.

Technology platforms, for their part, have been slow to implement comprehensive safeguards. Their business models prioritize engagement, focusing on views, clicks, and watch time — even when that attention comes at the expense of child safety. Critics argue that this creates an environment where harmful actors can operate under the radar, enabled by algorithms and insulated by a lack of regulation.

Legal responses have also struggled to keep pace with the evolving nature of the issue. Existing child protection laws often focus on overt abuse or trafficking, not the subtler, sustained exposure created by constant content sharing. In most states, there’s little recourse to stop or punish bad actors who exploit children’s likenesses or engage with child-focused content inappropriately.

As long as enforcement remains weak and penalties remain rare, online predators are likely to stay emboldened — hidden in plain sight, shielded by anonymity and platform inaction.

In the absence of stronger regulation or more proactive moderation, the burden of vigilance continues to fall on parents, creators, and viewers — often with too little support, and too much at stake.

The Performance of Innocence — for an Audience

Family channels rarely document childhood in its natural form. Increasingly, what they present is a curated — and often scripted — version of it, one shaped for algorithms, sponsorships, and maximum engagement.

In many cases, children are encouraged to perform on camera with the polish of seasoned influencers: pitching products, rehearsing gratitude, reenacting milestones, and projecting emotion on cue. The result is a stylized version of childhood — optimized for views, not development.

When their daily experiences get filtered through a performance lens, boundaries between real life and content can blur. Kids are learning to act before they’re learning to reflect, as their value becomes tied to audience response.

The consequences are already visible:

- Stalkers have reportedly shown up at fan meetups after identifying children’s locations through social content.

- Doxxing incidents involving child influencers have increased, often fueled by overshared personal details.

- Impersonation and roleplay using minors’ photos — including so-called “mommy roleplay” accounts — have been flagged across platforms.

- Digital kidnapping, where images of children are reposted and repackaged into fabricated family narratives, continues to be reported globally.

For many of these children, their online presence is permanent. Unlike traditional child performers, they often lack legal protections or a say in what is shared. Years later, they may enter adulthood with a trail of searchable content that includes their most personal, embarrassing, or traumatic moments — content they never consented to and may not be able to erase.

One striking example of this evolving landscape is The Sweet Sisterhood, a content house launched in 2025 featuring girls as young as eight, managed by their mothers to produce branded content across TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram. Styled shoots, scripted affirmations, and motivational catchphrases are staples of the collective’s content.

In a viral YouTube critique, creator Isabella Lanter voiced the growing unease: “These kids are not living normal lives. Their lives are surrounded by content, by performance, by what will do well with an audience…practically handing [pedophiles] content.”

The concern isn’t abstract. Child-focused content is routinely downloaded, cataloged, and redistributed on forums with predatory intent. In an era that incentivizes exposure and discourages restraint, the risks to child safety are systemic and increasingly difficult to ignore.

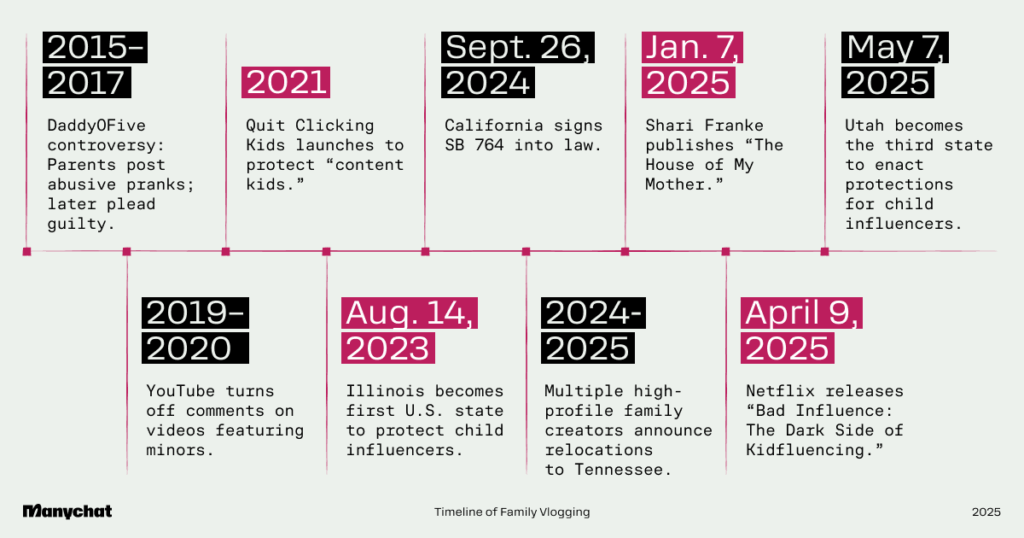

Timeline of Family Vlogging

Legal Change is Coming — but is it Enough?

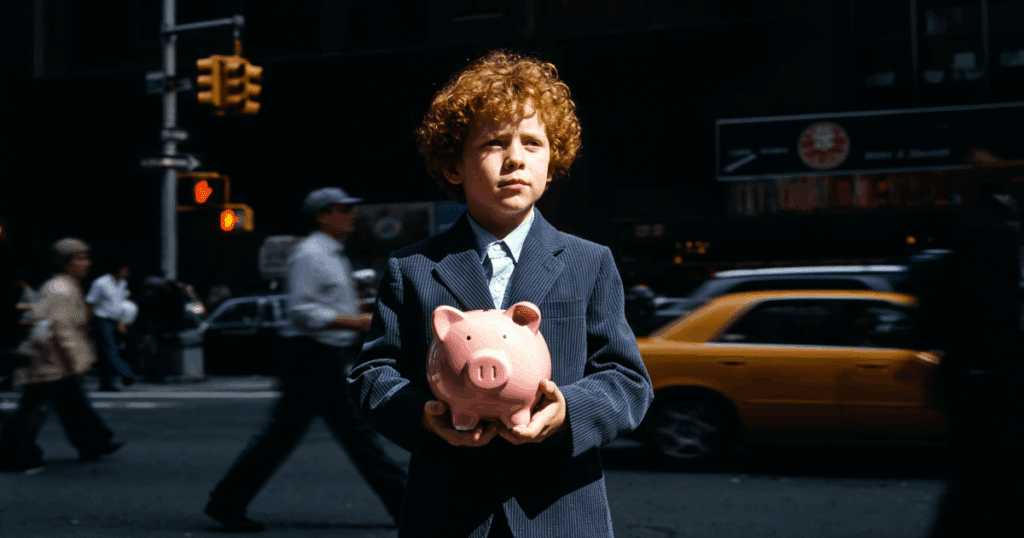

Lawmakers in the United States have begun to acknowledge what many digital rights advocates have long argued: children featured in monetized online content deserve both financial and personal legal protection.

The movement toward regulation gained momentum in 2023, when Illinois became the first state to pass legislation guaranteeing child influencers a share of their earnings. But it was California’s Senate Bill 764, signed into law in 2024, that sparked national attention — and, according to many observers, an influencer exodus.

Modeled after the 1939 Coogan Law (created to safeguard the earnings of child actors in Hollywood), SB 764 updates the framework for a new generation of child labor, one defined not by sound stages but by ring lights and Reels. The bill requires that if a child appears in 30% or more of a creator’s monetized content, 65% of earnings derived from platform revenue be set aside in a trust, accessible to the child once they reach adulthood.

On paper: progress

- Formal recognition that children featured online are labor contributors

- Guaranteed share (65%) of platform-generated income (e.g., AdSense, TikTok Creator Fund)

- Trust requirements ensure that children can access the money when they turn 18

Child advocacy groups lauded SB 764 as a step in the right direction. Even high-profile figures like Demi Lovato attended the bill signing to show their support for legislation aimed at correcting the current imbalance of power between content-creating parents and the children they feature.

In practice: loopholes and limits

However, critics argue that the law is toothless where it matters most. The bill does not cover brand partnerships, which often make up the majority of an influencer’s income. These direct sponsorships bypass platform monetization entirely and remain largely unregulated under SB 764.

There’s also the matter of enforcement. The law relies on creators to self-report content percentages and earnings. There is no dedicated watchdog agency tasked with auditing content or income streams, and many creators manage brand deals through personal LLCs, shielding the exact contributions of their children from scrutiny.

And for creators who prefer not to comply? The workaround is simple: relocate to a state without such laws. In the months following the passage of SB 764, a noticeable number of prominent family influencers (coincidentally!) announced moves to Tennessee, Texas, and Florida — states with no income tax and no comparable protections in place for influencers.

The Broader Legal Landscape

Illinois may have lit the first match, and California fanned the flames, but Utah soon followed with House Bill 322, which expands protections to cover children featured in family content and imposes time limits on how long they can be “on set.” Other states, including New York and Washington, have floated similar proposals.

Still, no U.S. law currently grants children the right to remove content about themselves retroactively. In contrast, the European Union’s “Right to Be Forgotten” gives individuals — including minors — the ability to request that search engines and platforms erase personal data under certain conditions.

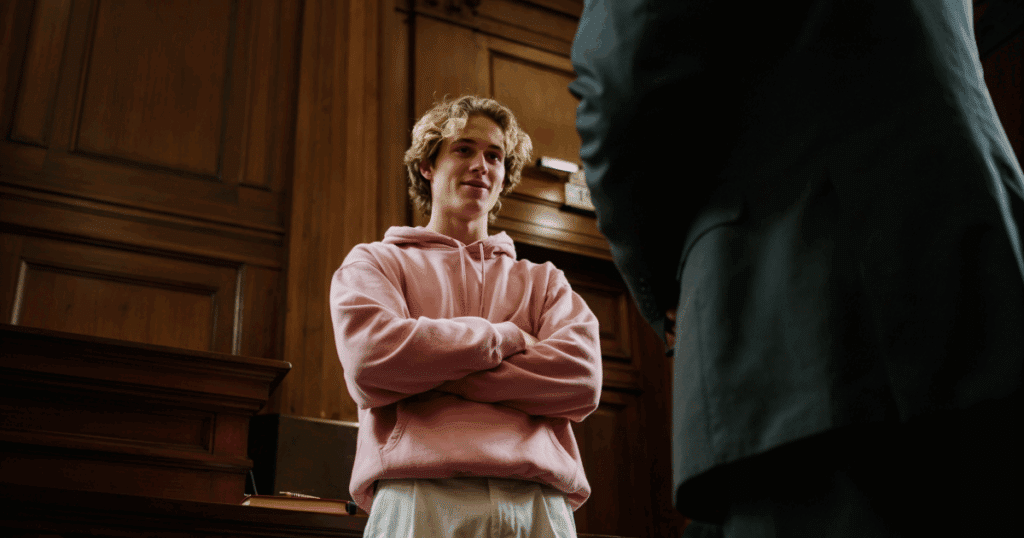

Family Court Meets the Creator Economy

Another unresolved question: What happens if a child wants to sue? Most of these laws do allow for legal recourse if a parent fails to comply with trust requirements. But bringing a lawsuit against your parents — especially as a newly independent 18-year-old — is not only emotionally fraught, but financially inaccessible for many.

In the meantime, the influencer economy continues to grow. And with more families entering the content space — some without awareness of these evolving laws — the responsibility for enforcement remains scattered and unclear.

Bottom line: Legal change is happening. But for many kids growing up on camera, it may still come too late — or never come at all.

Are Platforms Doing Enough?

There are some regulations in place, but critics argue most platforms prioritize engagement over protection. Here’s what each platform is doing as of this writing.

YouTube

- Disables comments on “made for kids” content.

- Demonetizes some child-centric videos.

- Still monetizes family channels in general.

TikTok

- Bans under-13s from having accounts.

- No specific protections for kids in other people’s videos.

- Comment moderation? Spotty.

- Restricts minors from public discovery (kind of).

- No consistent action is taken against family accounts featuring children.

- Still a hotspot for child modeling and lifestyle family content.

Meta recently expanded Teen Account Protections and Child Safety Features, but the language is vague — at what point in the mix of content does an account run by an adult “primarily feature children”? Parents or talent managers running accounts for kids are an obvious case, but it gets murkier for “adults who regularly share photos and videos of their children”. Does that include your neighbor’s monthly content dumps?

The platforms profit from this content. Regulation isn’t in their business model. But cultural pressure? That’s proving more challenging to ignore, and that’s where projects like the Tech Coalition’s Lantern program come in.

What Family Creators and Viewers Can Do

Despite a lack of real regulations, creators and consumers of content can still do a lot to improve things for young performers (because that’s exactly what they are).

For creators

- No vulnerable moments: Tantrums, punishments, or pain don’t belong online.

- Consent matters: If your kid can’t say no, it’s not a yes.

- Follow the law: If your state requires a trust, do it.

- Anonymize: Delay posts, blur faces, and avoid oversharing — especially in real time.

- Create “no camera” zones: bedrooms, school, or anywhere that should feel safe.

Bonus rule: Your kid is not your coworker.

For viewers

- Watch critically: If it feels wrong, it probably is.

- Don’t comment on kids: Even compliments get creepy fast.

- Report shady content: Especially if it violates platform rules.

- Support ethical creators: Reward people who don’t treat their child like a brand.

Protecting the Next Generation of Internet Kids

The camera isn’t inherently evil. But turning childhood into a monetized commodity is. If your baby’s first words are “like and subscribe,” something’s broken.

Over the last two decades, the concept of documenting family life for a public audience has evolved from scrapbook-style blogging to full-blown influencer empires. And for many families, the pressure to produce — more content, more engagement, more growth — often means turning childhood into a performance.

We’re finally seeing laws, memoirs, and movements call out what once passed as entertainment. The shift won’t happen overnight, but it’s happening — through regulation, yes, but also through public refusal to clap for exploitation.

Some creators are already adapting. More families are choosing not to show their children’s faces. Others limit their appearances to special occasions or use private settings and paid subscriptions to reduce the scale of exposure. But many still operate under outdated assumptions — that if a moment is filmed at home, it must be harmless.

That assumption no longer holds.

If childhood is becoming one of the internet’s most profitable genres, it should also become one of its most protected. That means stronger laws, yes — but also a more conscious audience. One that rewards boundaries over voyeurism, consent over clicks.

It starts with a simple test: Would I be okay if this were my childhood? If the answer is no, the next step is clear.

Because if the footage is forever, so is the responsibility.